Learning about dynamics of race and gender is an integral part of any student’s education and necessary to understand U.S. history. But instead of fostering an open and honest dialogue, a handful of states — including Texas, Tennessee, Idaho, and Oklahoma, among others — are passing censorship bills that ban conversations about race and gender in public schools. These bills chill students’ and educators’ First Amendment right to learn and talk about the issues that impact their everyday lives. They further marginalize communities, create an unsafe learning environment, and shortchange students of their right to receive an inclusive education, free from censorship or discrimination.

Anthony Crawford, Regan Killackey, and Lilly Amechi are part of a group of students and educators who sued Oklahoma for its censorship bill, HB 1775, which passed in May. Their stories show how the bill has already had a detrimental impact in classrooms and campuses and why learning about race and gender benefits all students, no matter their background.

AJ Stegall

Anthony Crawford

Anthony Crawford is a teacher at Millwood High School in Oklahoma City.

It’s not the first time America has tried to eradicate certain truths out of history books. When I was a junior in high school, I was kicked out of AP History class when I asked the teacher when we were going to learn about Black history. It was Black History Month, and we weren’t learning anything about any Black people. My question made the teacher uncomfortable. I remember his face turning red. He said, ‘You’re not going to disrupt my class, so please step out.’ So I tossed the books on the floor and left the class.

My students are the ones who want to talk about race and gender, because these are the issues they deal with in their everyday lives.

Later, when I became a teacher, the first thing I noticed was that students still didn’t have a clue about what was going on in society. They didn’t understand what happened during the Jim Crow era. They didn’t understand Reconstruction. They didn’t understand slavery one bit. So I made it my goal to catch them up and equip them with the knowledge they need to navigate society when they graduate. That means creating a curriculum that incorporates readings on race and gender and gives them an accurate picture of history and the systems that created the realities we see today.

Most of the time, my students are the ones who want to talk about race and gender, because these are the issues they deal with in their everyday lives. It helps them make sense of what they witness when they step outside school, like police brutality, mass incarceration, and the school-to-prison pipeline. It also helps them understand themselves, their communities, and each other.

AJ Stegall

AJ Stegall

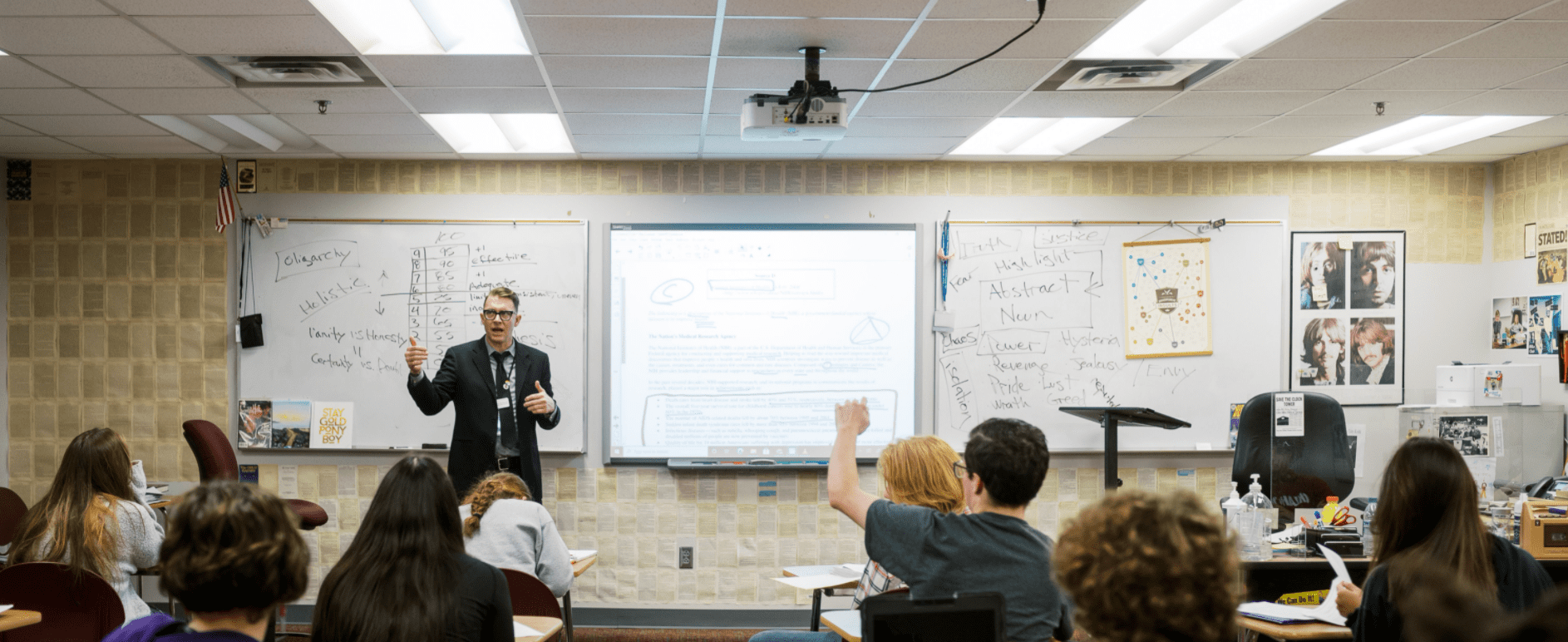

Regan Killackey

Regan Killackey is an English teacher at Edmond Memorial High School in Edmond, Oklahoma.

As an English teacher, my classroom discussions often center themes of race, sex, gender, and equity. These discussions are critical to my students’ understanding of literature, society, and each other.

Most importantly, as a teacher, I must ensure all my students can see themselves reflected in course material — not just the white students. When we unpack To Kill A Mockingbird and Their Eyes Were Watching God, my Black students get to reflect on pieces of their stories by connecting with the author and content within the narrative, which is critical for their development. Their peers — often for the first time learn through literature what it is like to be Black in America and the discrimination that my Black students and students of color experience every day. To share that experience with others is empowering for my students. Students of color and from other marginalized communities should have their voices heard in a predominantly white classroom. A diverse authorship and the themes that necessarily accompany it allow them the space to do that.

School officials instructed us to avoid books by authors of color and women authors, leaving two books by white men — The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald and The Crucible by Arthur Miller — as our only remaining anchor texts.

Oklahoma’s HB 1775 causes school districts to distrust teachers’ ability to lead these discussions, and as a result, schools are attempting to silence teachers for fear we may violate the bill. School officials specifically instructed us to avoid books by authors of color and women authors, leaving two books written by white men — The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald and The Crucible by Arthur Miller — as our only remaining anchor texts. English teachers in my district can possibly face formal admonishment or lose their Oklahoma teaching licenses if they don’t comply with this directive and are found to be in violation of HB 1775.

As a result of the censorship bill, my school is endorsing a whitewashed version of English literature that is detrimental to all my students and prohibits me from providing an inclusive education to the next generation of responsible citizens. In essence, it prohibits me from doing my job.

AJ Stegall

Courtesy of Lilly Amechi

Lilly Amechi

Lilly Amechi is a student at the University of Oklahoma (OU) and a member of the Black Emergency Response Team (BERT), an independent organization of Black student leaders dedicated to creating a safer and more supportive university experience for Black students.

After two racist incidents in February 2020, BERT led a sit-in and created a list of demands for OU. One of those demands was to create a new diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) course that would enable students to be more aware of how bias and discrimination impacts minorities. When HB 1775 was passed, OU no longer made the course a requirement. I think the impact will be detrimental to all students. And, to students of color, it sends a message that there is no willingness for people to understand our experiences.

To students of color, it sends a message that there is no willingness for people to understand our experiences.

The reality is that race pervades the classroom even when it’s not the main subject. In a political science class, we discussed President Andrew Jackson’s role in the Trail of Tears, a mass atrocity committed against Indigenous people, without acknowledging the horrors they faced and continue to experience today.

I’ve been similarly uncomfortable during conversations about slavery. In one class, a student argued that the Three Fifths Compromise is evidence that the Constitution is anti-slavery because it could have not counted slaves as people at all. These kinds of ignorant and racist comments create an uncomfortable learning environment for students of color. The censorship bill will make it worse because it targets anti-racist messages and viewpoints.

A student march at the University of Oklahoma.

Courtesy of Lilly Amechi

The university also removed a sexual harassment training as a requirement supposedly in order to comply with the censorship bill. The training teaches students about consent, respect, and human decency. It is rape and assault prevention. Sexual assault has also been a huge worry for women on campus, and particularly Black women, women of color, and LGBTQ+ women, and we are already seeing the negative effects of no longer requiring this training.

The sexual harassment training and DEI course served as early interventions for students who might consciously or unconsciously engage in harmful behavior. Now we feel we are much more on our own trying to stand firm and push back.

The reality is that race pervades the classroom even when it’s not the main subject.

In October, Anthony, Regan, and Lilly were among a group of students, teachers, and organizations that sued the state of Oklahoma with representation from the ACLU, the ACLU of Oklahoma, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and pro bono counsel Schulte, Roth & Zabel. The other plaintiffs include the Black Emergency Response Team (BERT); the University of Oklahoma Chapter of the American Association of University Professors (OU-AAUP); the Oklahoma State Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP-OK); and the American Indian Movement (AIM) Indian Territory.