- Publications >

- Report

Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect Law and the Criminalization of Motherhood

Document Date: November 29, 2020

When Kerry Lalehparvaran, a Black woman, awoke late one night in January 2015 to find her boyfriend gone from their room, she got up to find where he had gone. She found him standing over her daughter, hands on her shoulders, holding her down as she whimpered. Kerry fought to get him off her, but he fought back and dragged her down the hallway. He then started spanking her daughter. Kerry put herself between her daughter and the swinging belt, but the swings kept coming. Eventually, he managed to take Kerry’s keys and phone and lock himself and her daughter in the bedroom.

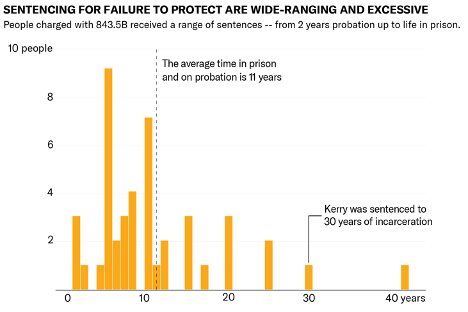

When she tried to escape the house to find help, her boyfriend heard her and physically prevented her from leaving the house. The next morning, Kerry’s roommate arrived and upon seeing the situation, fought the boyfriend, but lost when her keys and wallet were taken away. She eventually managed to escape and called the police, who arrested Kerry’s boyfriend and took her to Tulsa’s child advocacy center where the State took custody of her two youngest children, including her abused daughter. Kerry was arrested a week later for failing to protect her daughter, while her own back still bore the bruises of intercepting the swings of her boyfriend’s belt. Her boyfriend was convicted of child abuse and sentenced to 18 years in prison with 7 years of probation. Kerry was sentenced to 30 years in prison for failing to stop his abuse.

Situations like Kerry’s are common in Oklahoma, where the incarceration rate of women is the highest in the world – and has been for decades. In addition to relying heavily on incarceration to disrupt behavior, Oklahoma has a culture of holding women responsible for child-rearing. When children are abused, women are criminalized for surviving. For many women, especially women of color – whether they report or seek care for themselves – the moment they become involved with the criminal legal system, their own victimization is criminalized and their children taken away. In many cases, like with Kerry, women are victims of the same abuse for which they are incarcerated.

Specifically for Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect Law, where a caretaker is charged with failing to protect a child from someone else’s abuse, women are sentenced to an exuberant and wide-ranging amount of time in prison.

“I Didn’t Permit Anything” – The Incarceration of Kerry Lalehparvaran1

Long before the incident leading to her arrest, Kerry was the target of her boyfriend’s abuse. He reacted violently toward her. He threatened to kill her. On more than one occasion, he stuck a gun in her mouth. Her life was a state of constant fear and anxiety.

However, Kerry and her boyfriend were prosecuted as co-defendants. They had the same prosecutor and the same judge. The prosecutor refused to offer either of them a deal, asking for the maximum sentence for both child abuse and failure to protect – life in prison. Kerry’s boyfriend eventually pled guilty to child abuse after spending a year in jail.

Kerry decided to fight her case. “I wasn’t going to do anything but take it to trial,” Kerry said. “I wasn’t going to plead guilty to something I didn’t do….I didn’t permit anything.”2 Kerry’s case went to trial almost a year after her boyfriend was sentenced and two years after she was arrested. Despite Kerry’s boyfriend receiving a total of 25 years for child abuse, the prosecutor continued to argue that Kerry should receive life in prison for failing to stop it. To support her request for the maximum sentence, the prosecutor stated, “Well, she’s her mother.” Kerry was sentenced by a jury to 30 years in prison, a sentence that would keep her away from her children during the most important years of their lives and likely keep her locked up for the rest of her reproductive years.

Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect

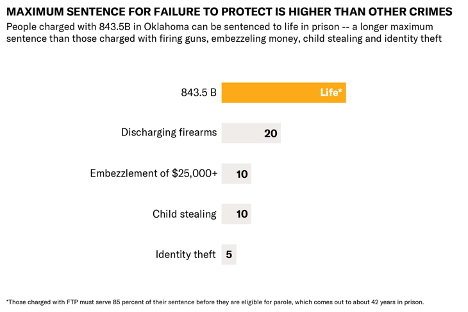

Oklahoma has criminalized the failure to prevent or report child abuse since 1963. The crime carries a maximum of life, which is high compared to other crimes.

The law applies not only to parents or guardians, but to any person. It doesn’t take into account situations like duress or experiencing domestic violence from the person committing the child abuse. While the child abuse itself must be “willful or malicious,” Failure to Protect only requires that the person “knows or reasonably should know” of a “risk” of child abuse.

To show that a person should have known of a risk of child abuse, Oklahoma prosecutors explicitly use sexist expectations of gender roles. They argue that a woman should have known the risk of child abuse under the assumption that mothers are responsible for child care and should notice immediately if anything is wrong.

Prosecutors have also argued that a woman should have known the risk because she was in an abusive relationship with the man accused of child abuse – essentially using the fact that she survived violence as evidence that she knowingly permitted child abuse. This is untrue. Domestic violence is about power and control. People enduring domestic violence are told repeatedly that the abuse and violence they are experiencing is their fault and eventually, they believe it. Because people experiencing domestic violence believe the abuse is their fault, it is not logical for them to assume that the violence is extending to their children. In their eyes, they are deserving of the abuse; their children are not.

Authors and supporters of Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect Law state it was written to incentivize people in abusive relationships to leave and that it is necessary to protect Oklahoma’s children. Experience has shown that neither is true. Leaving an abusive relationship is not as simple as walking out the door. Fear of the person responsible for the abuse,3 lack of financial resources,4 isolation from support systems,5 distrust of the legal system,6 and guilt and shame around experiencing7 abuse all act as barriers to seeking help. Deciding to leave can be extremely difficult, and leaving creates its own dangers. The risk of being killed by an abusive partner increases significantly when a person attempts to leave.8

Ultimately, Failure to Protect places an additional barrier to seeking help. People in abusive relationships fear they will be criminally prosecuted if they come forward about their abuse. They also fear losing custody of their children, which can result in foster care placement.

Who Is Incarcerated

Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect Law is used almost exclusively against women. ACLU’s Analytics team analyzed Oklahoma’s online court network data and found that women make up 93 percent of people convicted of failure to protect in Oklahoma. In the three percent of cases where a man is convicted of failure to protect, so was their female partner, because the prosecution simply did not identify the person committing the abuse and charged both caregivers with failure to protect. There were zero cases where a woman was convicted of child abuse and her male partner was convicted of failure to protect.

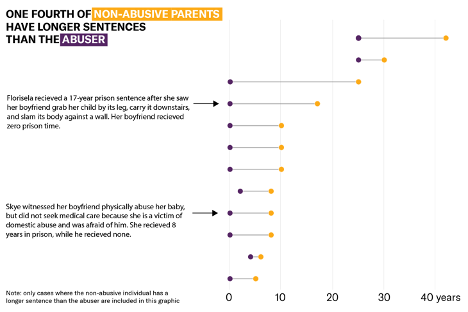

Not only are women held criminally responsible for the behavior of their male partners, they are often punished more harshly for it. One in four women convicted of failure to protect will receive a longer sentence than the person responsible for the abuse.

At least 50 percent of women convicted of failure to protect – including Kerry – were also abused by the same man who abused their children. Rather than receiving resources and support, they are prosecuted as co-defendants. Often, survivors of domestic violence are then incarcerated for failing to stop the crimes of their abusive partners and are separated from their children.

Kerry Lalehparvaran’s case is tragic and unjust. And it is not unique.

The ACLU, along with partnering organizations for criminal justice reform and women’s rights, are currently trying to end the criminalization of motherhood and the incarceration of survivors of domestic violence in Oklahoma. We are doing this in two ways: by attempting to reform Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect Law and by freeing women currently incarcerated for failure to protect10. In 2019, the ACLU of Oklahoma successfully freed domestic violence survivor and mother, Tondalao Hall, from prison after serving 15 years of her 30 year sentence for failure to protect. But this is only the beginning.

Countless other women like Kerry Lalehparvaran remain behind bars, and many more are faced with failure to protect charges and the accompanying threat of life in prison every day. If Oklahoma is serious about reducing the incarceration rate of women and protecting survivors of domestic violence, prosecutors must stop incarcerating women for the actions of their partners. Lawmakers must also significantly lower sentencing maximum for failure to protect and take into account the experiences of survivors of domestic violence.

The women charged with failure to protect need resources and support, not prison time, and we will continue to fight to make that a reality.

- Kerry Lalehparvaran gave Megan Lambert and the ACLU permission to publish her story as written.1

- Interview with Kerry Lalehparvaran, 7 May 2019.

- 21 Okl.St.Ann. § 843.5 Child abuse--Child neglect--Child sexual abuse--Child sexual exploitation--Enabling—Penalties. B. Any parent or other person who shall willfully or maliciously engage in enabling child abuse shall, upon conviction, be punished by imprisonment in the custody of the Department of Corrections not exceeding life imprisonment, or by imprisonment in a county jail not exceeding one (1) year, or by a fine of not less than Five Hundred Dollars ($500.00) nor more than Five Thousand Dollars ($5,000.00) or both such fine and imprisonment. As used in this subsection, “enabling child abuse” means the causing, procuring or permitting of a willful or malicious act of harm or threatened harm or failure to protect from harm or threatened harm to the health, safety, or welfare of a child under eighteen (18) years of age by another. As used in this subsection, “permit” means to authorize or allow for the care of a child by an individual when the person authorizing or allowing such care knows or reasonably should know that the child will be placed at risk of abuse as proscribed by this subsection.

- Denise Hien & Lesia Ruglass, Interpersonal partner violence and women in the United States: An overview of prevalence rates, psychiatric correlates and consequences and barriers to help seeking, 32 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 48 (2009), at 50, 51 (Fear created by [intimate partner violence] acts as a barrier to seeking help. Two of the most prevalent reasons why women did not report were fear of retribution and threats toward their children.).

- Evan Stark, Re-presenting Battered Women: Coercive Control and the Defense of Liberty, Violence Against Women (2012) at 12 (“Control tactics also foster dependence by depriving partners of the resources needed for autonomous decision-making and independent living . . . .”); Id. at 10 (“Controllers isolate their partners to prevent disclosure, instill dependence, express exclusive possession, monopolize their skills and resources, and keep them from getting help or support.”).

- Evan Stark, Re-presenting Battered Women: Coercive Control and the Defense of Liberty, Violence Against Women (2012) at 10 (“Controllers isolate their partners to prevent disclosure, instill dependence, express exclusive possession, monopolize their skills and resources, and keep them from getting help or support.”).

- Zuzana Podana, Reporting to the Police as a Response to Intimate Partner Violence, 43 Czech Sociological Review 453 (2010) (Twenty five percent of women surveyed said they didn’t report their abuse to the police because of the tendency of the police to minimize seriousness of incidents. Twenty nine percent of women do not report because of the belief that police do not take IPV seriously. Many women fear that police will make a double arrest. Ethnic minorities in particular do not report because of fear that DHS will take their children away.); Denise Hien & Lesia Ruglass, Interpersonal partner violence and women in the United States: An overview of prevalence rates, psychiatric correlates and consequences and barriers to help seeking, 32 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 48 (2009), at 15 (At the prosecution level, victims are often blamed.); Id. at 51, 52 (Poor black women are the most likely to experience re-victimization after initiating legal action, perhaps because of unresponsiveness of the police to their needs.).

- Deborah L. Rhatigan et al., The Impact of Posttraumatic Symptoms on Women's Commitment to a Hypothetical Violent Relationship: A Path Analytic Test of Posttraumatic Stress, Depression, Shame, and Self-Efficacy on Investment Model Factors, 3 Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 181 (2011) 183 (“[V]ictimized women, particularly those suffering from psychiatric conditions like PTSD or depression, may struggle to obtain adequate alternatives because of tendencies toward anger or withdrawal. Even with repeated attempts at obtaining those resources, women’s feelings of shame may increase because of negative experiences with informal or formal sources of support (i.e., via victim-blaming); Emma Williamson, Living in the World of the Domestic Violence Perpetrator: Negotiating the Unreality of Coercive Control, 16 Violence Against Women 1412 (2010) at 1417 (“Women who experience domestic violence expect to be hated because they have learned to hate themselves.”); Melissa E. Dichter, Associations Between Psychological, Physical, and Sexual Intimate Partner Violence and Health Outcomes Among Women Veteran VA Patients, 12 Social Work in Mental Health (2014) at 414 (“Sexual violence victims also often feel shame, humiliation, and degradation and experience stigmatization and blame for their victimization.”).

- Adam Pritchard et al., Nonfatal Strangulation as Part of Domestic Violence: A Review of Research, Trauma, Violence, & Abuse (2015).

- The Oklahoma Women’s Coalition advocated for legislative reform of Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect bill during the 2019 legislative session. The bill would have added an affirmative defense of duress to the crime and reduced the maximum sentence for failure to protect from life in prison to four years, the same maximum sentence as child endangerment. However, the bill was unsuccessful due to the lobbying efforts of Oklahoma’s District Attorney’s Council. Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform, through their Commutation Campaign, have applied for commutation on behalf of women incarcerated for failure to protect. Their applications will go before Oklahoma’s Pardon and Parole Board. If they receive a favorable vote from the Board, their applications will go before the Governor for his signature. Still She Rises, a holistic defense non-profit in Tulsa County, represents mothers charged with failure to protect and facing the loss of their children every day.

Methodology

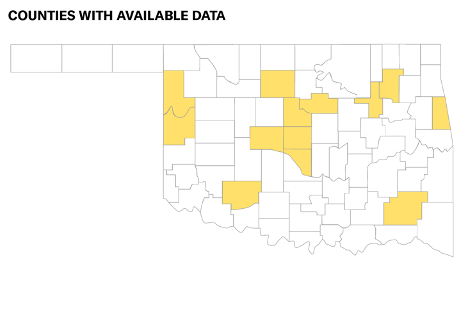

ACLU of Oklahoma contracted with Code for Tulsa to data scrape Oklahoma’s online court network (OSCN). Code for Tulsa did a search for terms relating to failure to protect for cases across Oklahoma from 2009 – 2018, the date the crime was recodified through the end of the year prior to the search.

While the data scrape included cases from all of Oklahoma’s 77 counties, only 13 counties supplied the data in a reliable and consistent format. The information given above relies upon information from those 13 counties.

ACLU of Oklahoma contacted the clerk of each county with a failure to protect conviction to request the probable cause affidavits for each case.

The cases discussed include only cases where the person was convicted of failure to protect. In none of the cases included in the analysis was the person also convicted of child abuse. In a few of the cases analyzed, the person was convicted of both failure to protect and child neglect, but only where the probable cause affidavit shows that the two charges are based on identical facts – the person’s failure to report child abuse to the police or to obtain medical care for the child quickly enough.

The gender of each person was estimated using the percentage of the US population with the same first name who are men as compared to the percentage who are women. For people sentenced to a term of incarceration, that estimate was verified by the data provided on Oklahoma’s Department of Correction’s website. The gender of a person was further verified on an individual basis by the pronouns used in the probable cause affidavit.

The information regarding the person who committed the child abuse in each was most often found because the person convicted of failure to protect and the person convicted of child abuse were prosecuted as co-defendants in the same case. When that was not the case, the person convicted of child abuse was identified in the probable cause affidavit of the failure to protect case. The details of their sentence were then found by an OSCN search.

Information about the occurrence of domestic violence was gathered in a number of ways. The first is where the person convicted of failure to protect told the ACLU of Oklahoma directly and in person during an interview. The second is where the person reported domestic violence as part of their subsequent commutation application. The third is where domestic violence was documented in the probable cause affidavit. The fourth is where the person convicted of failure to protect received a protective order against the person convicted of child abuse. Domestic violence was not recorded where a protective order was requested but not granted. Domestic violence was only recorded where the person convicted of failure to protect was a victim of the person convicted of child abuse, and not where the perpetrator of domestic violence was any other individual.

ACLU of Oklahoma manually looked up each failure to protect case on OSCN to obtain the sentencing information for the person convicted of failure to protect. While some cases included sentences for child neglect in addition to failure to protect, the data discussed above includes only the sentences for failure to protect. Deferred sentences and suspended sentences were calculated as probation. Life sentences were calculated as 42 years, the average number of years someone with a life sentence will spend in prison in Oklahoma before they are eligible for parole on an 85 percent crime.

All information discussed, with the exception of certain details of the facts leading up to Kerry Lalehparvaran’s arrest, are public record.

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.