I. Why are we here and how does it hurt Oklahoma?

Stable housing is the crux of a healthy life. But in Oklahoma, our laws foster unreliable and dangerous housing for the most vulnerable, particularly low-income tenants. When it comes to housing, Oklahoma’s law fails those most in need of help. It leaves low-income tenants1 living in dilapidated and dangerous apartments with no way out. Nor does it provide tenants any protection from uncaring landlords who retaliate against tenants for actions as simple as requesting repairs. And for those who do try to vindicate their rights in court, Oklahoma law leaves eviction courts severely underfunded, understaffed, and therefore without the resources to protect what housing rights do exist under Oklahoma law.

If low-income tenants live in dangerous conditions and have an uncaring landlord, they have no real solutions. While many Oklahoma landlords work diligently to provide safe housing, the percentage of out-of-state, corporate landlords has grown exponentially in recent years. That spike in out-of-state ownership has led to a sharp increase in the number of faceless landlords disconnected2 from the community. And if such landlords decide they don’t want to fix the flooding, mold, etc., Oklahoma law offers three options to a tenant, all of them dead ends:

- terminate the lease and leave,

- pay someone to fix it and deduct it from the rent (but only up to the cost of one month’s rent), or

- report the conditions to the city as municipal code violations and hope the city forces the landlord to make repairs.3

1 25% of Oklahoma renters are extremely low income, meaning their income levels are at or below the poverty line or only 30% of the median income for their area. Given the lack of affordable housing and increase in rents, 71% of extremely low-income renters in Oklahoma must spend more than 50% of their total income on housing. See Data from the National Low Income Housing Coalition, (last accessed on April 12, 2024) available at: https://nlihc.org/housing-needs-by-state/oklahoma

2 Katie Arata, Out-of-State Corporations are flooding Oklahoma Housing Market, KTUL Tulsa News, (June 22, 2022) available at: https://ktul.com/news/local/out-of-state-corporations-are-flooding-oklahoma-housing-market-real-estate-homeowners-state-representative-mickey-dollens-anti-retaliation-laws; Anna Pope, USDA Report Shows Foreign-Owned Land Holdings Rising in Oklahoma, KOSU (NPR) (Jan. 2, 2024) available at: https://www.kosu.org/local-news/2024-01-02/usda-report-shows-foreign-owned-land-holdings-rising-in-oklahoma

3 The law also includes two other options available if, and only if, the landlord fails to provide an essential service, including hot water, heating, electricity, gas, and running water. In these cases, the tenant’s two extra options are: (1) pay to have the missing essential service repaired and deduct its actual cost from the rent; or (2) vacate the current unit, find substitute housing, and be excused from paying rent until the essential service is restored. Option two is a nonstarter because of how difficult it is for low-income tenants to find any substitute housing, especially short-term housing. Option one can be helpful for tenants whose issues happen to include the loss of essential service. But the list of essential services is so limited that the vast majority of conditions issues fall outside the list.

Terminating the lease and leaving is a dead end because there is nowhere to go. Oklahoma has a severe lack of affordable housing, 77,000 units short of what it needs4. Even if tenants find a place, most low-income tenants lack the money to move. Repairing the issue and deducting the cost from that month’s rent is likewise a nonstarter because repairing most dangerous housing conditions will cost over one month’s rent. Low-income tenants cannot afford rent that exceeds six to eight hundred dollars a month. The cost of fixing any serious issue that threatens a tenant’s health will cost more than that. Replacing a dangerous mold infestation or replacing plumbing to fix a water leak are not cheap. Nor can tenants rely on repair and deduct when the issue is building wide in a multi-unit structure, such a broken staircase, faulty wiring, or mold. So, low-income tenants find themselves again at a dead end. Reporting the conditions to the city as code violations is a final option. But that decision can backfire and leave tenants on the street. As the above examples show, tenants have no way to require their landlord to make repairs. And Oklahoma’s major cities do not proactively inspect rental properties and enforce their housing codes. So uncaring landlords can ignore requests from tenants, avoid any need to stand up to routine inspection, and let the property dilapidate. By the time a tenant does report the conditions to the city, the building can be in such disrepair that the city condemns the entire building. The consequences of this system of code enforcement forced hundreds from their homes in Midwest City last year when the City condemned a large complex (owned by a California corporation) for dangerous conditions the corporation refused to repair.5

4 Data from the National Low Income Housing Coalition, (last accessed on April 12, 2024) available at: https://nlihc.org/housing-needs-by-state/oklahoma

5 Kaylee Olivas, Unsafe Conditions: Midwest City apartment complex condemned, families forced out, KFOR News, (June 21, 2023) https://kfor.com/news/local/unsafe-conditions-midwest-city-apartment-complex-condemned-families-forced-to-leave/ ; Jeff Harrison, Property owner has 30 days to address issues, Midwest City Beacon, (May 29, 2023) https://www.centraloklahomaweeklies.com/2023/05/29/midwest-city-declares-apartment-complex-dilapidated/

As for tenants who simply request repairs and hope their landlord does the right thing, they can find themselves in eviction court. Oklahoma is currently one of only six states in the nation without anti-retaliation protections for tenants.6 So, uncaring landlords who don’t want to make repairs can avoid the cost of repairs and take the cheaper option, filing an eviction. Eviction filing fees are so cheap across Oklahoma7 that evicting a tenant can be cheaper than any serious repair. And the uncaring landlord can rent the same unit back out to another desperate tenant because affordable housing is so scarce in Oklahoma.8

Our eviction courts must also change course, or more accurately, the state must provide the courts with the funding and time they need to change course. Low filing fees combine with two other elements—a mere five-day eviction timeline and underfunded court systems—to create eviction courts with few judges and an overflowing number of cases.9 The daily eviction court dockets in Oklahoma City hover around two hundred cases, all to be heard within a few hours.10 The result is as expected, overloaded and underinformed court proceedings where tenants have only days to prepare, a few minutes to speak to the judge, and 48 hours to move if evicted.11 These rushed processes can lead to error and incorrect outcomes, meaning courts erroneously evict people and contribute unnecessarily to the negative downstream effects of an eviction. Here, the fault is not on judges or court staff but on the state, for its failure to create realistic eviction timelines and properly fund courts that adjudicate such important issues.

The consequences do not stop with losing a home. Eviction is the sort of harm that multiplies fast, kicking off a cycle of trauma. Eviction naturally leads to one of two things: (1) homelessness; or (2) high rates of residential mobility—i.e. moving a lot.12 It’s either the street or find a way to move. It is no surprise then that the number of unhoused people taking refuge in local shelters has been shown to increase alongside eviction rates.13 As for those lucky enough to find a new place, that place will almost surely be in a worse neighborhood.14 Once an eviction is on a person’s record, many landlords will refuse to rent to them, driving tenants to cheaper neighborhoods with high “levels of poverty and violent crime” and “substandard living conditions.”15 And once there, the traumas of eviction lead to an increased likelihood of job loss and mental illness that often leads to yet another eviction, and the cycle continues.16 17

6 Sabine Brown, Renters Need Protection Against Landlord Retaliation, Oklahoma Policy Institute, (Mar. 15, 2023) https://okpolicy.org/renters-need-protection-against-landlord-retaliation/

7 Sabine Brown & Justice Jones, Oklahoma Legislators need to do more to expand access to housing, Oklahoma Policy Institute, (July 31, 2023) https://okpolicy.org/oklahoma-legislators-need-to-do-more-to-expand-access-to-housing/

8 Henry Gomory and Matthew Desmond, Extractive Landlord Strategies: How the private rental market creates crime hot spots, The Eviction Lab, (May 11, 2023) https://evictionlab.org/extractive-landlords-and-crime/

9 41 O.S. § 131 (allowing a landlord to bring an eviction action in court five days after the tenant’s failure to pay rent).

10 Andy Weber, Hundreds of Oklahoma county families could be evicted just days before Christmas, KOCO News, (Dec. 20, 2023) https://www.koco.com/article/oklahoma-county-eviction-numbers-christmas/46192504

11 Adam Hines, A Week to Prep, Two Minutes to Talk, and Two Days to Move: Why Oklahoma’s Eviction Courts Are Out of Step with the Constitution, 75 Okla. L. Rev. 939 (2023)

12 Gomory, supra note 5.

13 Dan Treglia, et al., Quantifying the Impact of Evictions and Eviction Filings on Homelessness Rates in the United States, Housing Policy Debate, (Mar. 31, 2023).

14 Matthew Desmond & Rachel Tolbert Kimbro, Eviction’s Fallout: Housing, Hardship, and Health, 94 Soc. Forces 295, 299 (2015).

15 Gomory, supra note 5.

16 Desmond, supra note 10.

17 Id. at 304.

II. How do we get out? - Three Steps to Affordable, Safe Housing in Oklahoma

Step 1. Anti-Retaliation, the Specific Performance Remedy, and Eviction Record Sealing

Anti-retaliation protections and a specific performance remedy would work together to encourage safe, habitable conditions in rental units. The specific performance remedy would grant tenants the power to ask the court to order a landlord to make the repairs necessary for habitable conditions. Anti-retaliation protections would prohibit landlords from retaliating against tenants for requesting repairs and/or using the specific performance remedy. Landlords will be far more likely to comply with repair requests from tenants armed with specific performance as a real threat and anti-retaliation as protection. As it stands, low-income tenants are left to the landlord’s whims. Specific performance and anti-retaliation would begin to rebalance the scales.

1.A – House Bill 2109

As currently written, Oklahoma H.B. 2109 would provide both anti-retaliation protections and the specific performance remedy.18 Last year, the bill made it out of committee, passed a House floor vote, but never made it to a vote in the Senate. Thankfully, the bill remains live this session, and given the potential impact of its changes, housing advocates are and should be pushing to pass it with minimal amendments. Retaliation against tenants comes in many forms, and the current version of H.B. 2109 addresses most of them. A landlord can retaliate against a tenant for requesting repairs, reporting housing code violations, or for something as simple as joining a tenants’ union. That retaliation can include increasing the tenant’s rent, decreasing services to the tenant, filing or threatening an eviction against them, and refusing to renew their lease. H.B. 2109 would protect tenants from all those forms of retaliation and more.19 If the tenant can convince the judge that the landlord’s actions were retaliatory, which means producing enough evidence to show that the action was more likely than not retaliatory, then the landlord would owe the tenant actual damages for their retaliatory conduct and have to pay the tenant’s attorney’s fees.20

The smaller but just as impactful provision of H.B. 2109 is the specific performance remedy. If (1) the housing conditions are dangerous to a tenant’s health and (2) the landlord fails to repair on their own within a reasonable time, the specific performance remedy would allow the tenant to ask the court to order the landlord to make repairs.21

18 H.B. 2109, http://www.oklegislature.gov/BillInfo.aspx?Bill=hb2109&Session=2300

19 H.B. 2109 § 1(A)(a)-(e)

20 H.B. 2109 § 1(B).

21 H.B. 2109 § 2 (amendatory section changing the language of 41 O.S. § 121 to create a specific performance remedy).

The primary obstacle to HB 2109 is messaging. It is essential to explain how HB 2109 protects tenants from predatory landlords without exposing good landlords to unnecessary litigation.

Thankfully, everything needed to disprove the deluge of frivolous retaliation claims already exists in the current text of H.B. 2109. The bill contains many exceptions to protect landlords, and taken together, they amply protect landlords from frivolous retaliation claims. Per the bill’s current text, retaliation claims fails if: (1) the tenant is behind on rent; (2) the tenant created unsafe or destructive conditions on the property; or (3) tenant is using the premises for an illegal purpose.22 And the landlord can make a broad “good faith” argument that they filed an eviction for non-retaliatory reasons.23 Landlords can likewise raise rent and avoid frivolous retaliation claims as long as: (1) they raise rent for all tenants equally; (2) the cost of compliance with legal regulations required an increase in rent; (3) the landlord made substantial improvements to the unit that justify raising rent; and (4) the landlord raises rent during lease renewal “in the standard course of business.”24 Those are only some of the protections offered landlords in the bill. And the broad protections such as the “good faith” argument and raising rent “in the standard course of business” give landlords significant leeway to disprove frivolous claims and even resist legitimate ones. That outcome is not ideal for tenant advocates, especially since landlords have lawyers to make strong arguments in court far more often than tenants. But based on conversations with other housing advocates, these compromises seem essential to passing the bill.

1.B Eviction Record Sealing

In Oklahoma, eviction records haunt tenants forever. Once a tenant has an eviction filed against them, it is forever publicly accessibly information via the Oklahoma State Courts Network (OSCN). So, one bad financial mishap in a person’s twenties can make securing housing harder for the rest of their lives. The lingering effects of an eviction record are so persistent that it has come to be called the “Scarlet Letter E.”25 It works to trap families in a lower caste of society where the only landlords willing to rent to them are those in the least desirable and more dangerous neighborhoods. Granting tenants the grace the overcome and escape past mistakes is essential for creating fair housing opportunities in Oklahoma. But here, there is good news. Awareness around this issue is growing, and Rep. Swope of Tulsa introduced a bill this year (2024) that would allow for sealing eviction records three years after the filing.26 Even though the bill lost traction this year, with ongoing advocacy and awareness, eviction record sealing can be a reality in Oklahoma.

22 H.B. 2109 § 2(C)-(D).

23 Id.

24 H.B. 2109 § 2(E).

25 Heather Warlick, Oklahoma Evicted: Thousands of Civil Filings Linger in Records Forever, Oklahoma Watch (Feb. 27, 2024), https://oklahomawatch.org/2024/02/27/oklahoma-evicted-thousands-of-civil-filings-linger-in-records-forever/#:~:text=Oklahoma%20courts%20are%20reluctant%20to,on%20from%20their%20financial%20problems.

26 S.B. 2121, http://www.oklegislature.gov/BillInfo.aspx?Bill=hb2121&Session=2400

Step 2. City-Level Changes – Zoning, “Responsible Parties Lists,” and a Municipal Right to Counsel

State law changes like H.B. 2109 are necessary but insufficient to resolve the eviction crisis. Tenants cannot live in safe, affordable conditions if local zoning ordinances make sufficient affordable housing impossible. Nor can tenants be expected to do all the work of ensuring habitable conditions. The specific performance remedy will only work for tenants savvy enough to navigate the court system. But “responsible parties lists” would allow city governments to track property ownership and proactively enforce housing codes. And even with anti-retaliation laws and the specific performance remedy, most tenants will be left to use those protections without the help of a lawyer.27 Thankfully, that problem also has a solution. Some cites are implementing a municipal right to counsel, ensuring that all tenants have representation.

2.A - Zoning & the Affordable Housing Crisis in Oklahoma

Effecting zoning change in Oklahoma is a city government issue. Political pressure on city governments is both the quickest and perhaps the only way to change these zoning laws. The Oklahoma Policy Institute is doing great work gathering the necessary data, but political organizers will have to start showing up at meetings, mounting social media information campaigns, and holding community meetings to rally political support for change. The support of the community and of city officials is crucial.

This lack of affordable housing also has legal roots. Municipal zoning laws determine where different types of structures can be built. And these decisions influence the available stock of affordable, low-income housing. Low-income housing requires multi-unit properties. So, cities with laws that severely limit multi-unit residential properties artificially restrict the supply of low-income housing. Restricting the supply drives up the cost of the low-income housing that does exist and leaves many with no affordable place to go.28 Sadly, Oklahoma City and Tulsa do just that, and as a result, both cities (and the state as a whole) have an enormous affordable housing deficit. Ninety-six percent of Oklahoma City’s residential areas are zoned to allow for single-family units only, leaving multi-unit residential properties to squeeze onto four percent of OKC’s residential land.29 Tulsa and Norman are similarly bad with eighty-one percent and ninety-eight percent respectively of residential land zoned for only single-family properties. But many cities have changed course and expanded zoning for multi-unit properties, and as a result, low-income housing numbers increased, and the rate of rent hikes slowed.30 Oklahoma’s cities can and should do the same.

27 Sabine Brown, Plain language eviction summons can help Oklahomans in eviction court, Oklahoma Policy Institute, (Feb. 28, 2023) https://okpolicy.org/plain-language-eviction-summons-can-help-oklahomans-in-eviction-court/

28 Sabine Brown, Ending single-family zoning would help close Oklahoma’s housing gap, Oklahoma Policy Institute, (Dec. 14, 2023) https://okpolicy.org/ending-single-family-zoning-would-help-close-oklahomas-housing-gap/

29 Id.

30 Alex Horowitz & Ryan Canavan, More Flexible Zoning Helps Contain Rising Rents, Pew Research Center, (April 17, 2023) https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2023/04/17/more-flexible-zoning-helps-contain-rising-rents?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=eb6dbd75-1ed1-4af6-b51d-6511649674ae

2.B - Responsible Parties Lists to enforce habitability standards

Cities across the country have enforced safe conditions for rental properties with responsible parties lists.31 These cities require all property owners to register their name and contact information with the city. This information allows cities to contact property owners and conduct proactive, routine inspections to ensure compliance with local housing codes.32 Support for this approach has been widespread in Texas, including the City of Dallas who implemented the program in 2017 with a near uniramous and bipartisan vote.33 Texas has at least fourteen cities with rental registries.34 Without these lists, tenants are left to enforce housing codes on their own and report violations after the fact. That approach not only leaves tenants open to retaliation under current law but also means many issues go unreported until they become severe, leading to outcomes like that at a recent Midwest City property where the city condemned the entire property and forced hundreds of tenants onto the streets.35

But even if Oklahoma City or any other city in Oklahoma wanted to create a responsible parties list, Oklahoma is the only state in the county with a law prohibiting municipalities from creating such a list.36 In 2014, the Oklahoma Association of Realtors successfully advocated for the bill, claiming it was only a guise for cities to collect unnecessary fees.37 But these lists serve an important purpose. Because tenants will never be able to entirely enforce habitable conditions on their own, empowering cities to proactively address the issue is an essential step toward affordable, safe housing for everyone.

31 Preston Brasch, Common sense reforms needed to protect Oklahoma tenants, Oklahoma Policy Institute, (May 9, 2017) https://okpolicy.org/common-sense-reforms-needed-protect-oklahoma-tenants/

32 A Guide to Proactive Rental Inspections, Change Lab Solutions (2014), https://www.changelabsolutions.org/product/healthy-housing-through-proactive-rental-inspection

33 Tristan Hallman, Dallas makes rules tougher on landlords with new housing standards, The Dallas Morning News (Sep. 28, 2016), https://www.dallasnews.com/news/2016/09/28/dallas-makes-rules-tougher-on-landlords-with-new-housing-standards/ (highlighting the 12-1 city council vote that passed the city’s property registry with support from traditionally conservative and traditionally liberal city council districts).

34 Preston Brasch, Common sense reforms needed to protect Oklahoma tenants, Oklahoma Policy Institute, (May 9, 2017) https://okpolicy.org/common-sense-reforms-needed-protect-oklahoma-tenants/

35 Olivas, supra note 3.

36 11 O.S. § 22-101.1

37 Small Business Owners Won’t have to Pay a Fee to Register Vacant Land, National Federation of Independent Business, (May 27, 2014) https://www.nfib.com/content/news/oklahoma/small-business-owners-wont-have-to-pay-a-fee-to-register-vacant-land-65735/

2.C - The Municipal Right to Counsel in Evictions

Truly fair housing courts are only possible with a right to counsel for tenants. Tenants, especially low-income tenants who most often face eviction, rarely have the money for an attorney. Whereas, landlords, especially corporate landlords who evict the most, have attorneys most of the time.38 And resolving this power balance can only realistically be done at the city-level. With a federal right to counsel in civil cases sitting long dead (and unlikely to be revived) and states unlikely to take on the cost of representation state-wide, cities are left as the ones with the necessary money and political will to achieve right to counsel. Two Midwestern cities were the first to take it on. Kansas City, Missouri adopted a right to counsel in evictions in 2022, and St. Louis, Missouri followed suit, passing the ordinance in 2023 with a start date in 2024.39 Kansas City’s program has showcased just how impactful right to counsel can be. In the first four months, four hundred tenants used the service, and 89% of them had their cases dismissed, meaning they either got to stay in their homes or negotiated a move-out agreement and avoided an eviction on their record.40 Still, the financial costs of these programs are significant and will require consistent political support. By late last year, Kansas City’s team of twelve attorneys was overwhelmed and forced to turn people away.41

Building the political support necessary to create and continually fund such a program will be another feat for organizers, change-makers, and city government leaders. Thankfully, Legal Aid Services of Oklahoma (LASO) is already setting a necessary precedent and gathering data. With the help of grant funds, LASO has established the capacity to represent most tenants in Oklahoma City and Tulsa who want representation.42 The data from LASO efforts will provide insight into the effects of right to counsel and will inform Oklahoma City and Tulsa as they, hopefully, consider funding this program long term. To succeed, local organizers and city government leaders will need to help, speaking up at city council meetings and engaging the public to build support for the program. Without the right to counsel, many low-income tenants won’t even be able to use protections like anti-retaliation and a specific performance remedy. We must pass those reforms first. That’s why they are step one. But a right to counsel is a must for housing equity long term.

38 Providing legal representation could begin to fix Oklahoma’s broken eviction process, Oklahoma Policy Institute, (Aug. 10 2020) https://okpolicy.org/providing-legal-representation-could-begin-to-fix-oklahomas-broken-eviction-process/

39 Malik Jackson, Kansas City leaders say right to counsel program a success, Fox 4 News, (Oct. 12, 2022), https://fox4kc.com/news/kansas-city-leaders-say-right-to-counsel-program-a-success/ & St. Louis Enacts Right to Counsel, Becoming Second city in Missouri to Pass RTC Ordinance, National Low Income Housing Coalition, (Oct. 2, 2023), https://nlihc.org/resource/st-louis-enacts-right-counsel-becoming-second-city-missouri-pass-rtc-ordinance

40 Jackson, supra note 39.

41 Mili Mansaray, Rising rents leave more Kansas City tenants facing eviction, The Kansas City Beacon, (Sept. 18, 2023) https://kcbeacon.org/stories/2023/09/18/kansas-city-rent/

42 Richard Mize, Legal aid help for renters facing eviction in Oklahoma City is working and being expanded, The Oklahoman, (Dec. 18, 2023), https://www.oklahoman.com/story/business/real-estate/2023/12/18/more-renters-facing-eviction-in-okc-can-get-help-with-free-legal-aid-after-right-to-counsel-extended/71891637007/

Step 3. Equitable Courts - Extending the Eviction Timeline and Increasing Filing Fees.

Even if the state legislature and cities fulfill the need for reform, those reforms can only play out in a fair environment if the housing courts themselves are fair. As of now, cheap filing fees have made court the first option for landlords, leading to a high number of eviction filings that turn out to be unnecessary. These frivolous eviction filings overwhelm eviction courts in Oklahoma’s urban areas, cutting into the time necessary to fairly adjudicate the necessary evictions. That slim time in court means neither the parties nor the judge have the time necessary to explain and decide the case.43 So even with big wins like state law protections and a city-level right to counsel, overwhelmed courts will still result in unnecessary evictions and all their harmful aftereffects. Thankfully, a few different avenues could cut down on the number of unnecessary evictions and ensure judges have the time necessary to fairly adjudicate cases.

3.A Increasing Filing Fees & Extending the Eviction Timeline

Unsurprisingly, landlords file more evictions when filing fees are cheap.44 The surprising piece is just how drastically filing rates drop with a fee increase.45 When researchers cross-referenced the eviction rates and eviction filing fees with cities across the country, the difference was stark. Even after controlling for other factors, the data showed that a $100 increase in eviction filing fees nearly halved the number of eviction filings.46 And the effect is even stronger for majority-Black neighborhoods, demonstrating a 357% decrease in filing rights.47 Such a strong decrease in filings with only an extra $100 suggests that many filings under cheap fee structures are unnecessary. In fact, data from Oklahoma shows that the most common outcome in an eviction case is a landlord dismissing the case themselves.48 Filing is so cheap in Oklahoma ($58) and evictions can be filed so quickly (when rent is five days late) that landlords file evictions prematurely, clog up the court docket, and end up dismissing when the tenant pays.49 So, both national and local data emphasize how much a fee increase would lighten the load on our underfunded court system.

43 Kathryn Ramsey Mason, Housing Injustice and the Summary Eviction Process: Beyond Lindsey v. Normet, 74 Okla. L. Rev. 391, 415-16 (2022).

44 Gomory, supra note 17.

45 Id.

46 ”To conduct their analysis, the authors compared eviction filing costs with eviction filing, eviction judgement, and serial eviction filing rates at the neighborhood level (census tracts), while controlling for other factors such as rental market characteristics, tenant protection laws, political context, race, income, and household composition.”

47 Id.

48 Adam Hines, Case by Case: A Study of Oklahoma’s Eviction Courts and A Path Toward Equity, Oklahoma Access to Justice Foundation, 7 (Aug. 2022).

49 Sabine Brown & Justice Jones, Oklahoma Legislators need to do more to expand access to housing, Oklahoma Policy Institute, (July 31, 2023) https://okpolicy.org/oklahoma-legislators-need-to-do-more-to-expand-access-to-housing/

Pairing a fee increase with an extended eviction timeline would pull double duty, further decreasing the number of filings and keeping more tenants in their homes. The Oklahoma Policy Institute has created a great infographic showcasing how Oklahoma’s accelerated eviction timeline leads to more unnecessary evictions.50 The short version is: when tenants have fourteen days to pay before an eviction (like they do in cities like Nashville) they naturally come up with the money more often; whereas Oklahoma tenants, who have only five days, often lack the time to find the money, leading to more eviction filings. That structure helps explain why Tulsa and Oklahoma City are in the top twenty most-evicting cities, and Nashville is eighty-seventh on the list.51

Increased filing fees and extended timelines would both require a change in state law. Thankfully, progress on this change is already underway. In 2023, a bill increasing filing fees and timelines was introduced.52 While that bill did not make it out of committee, advocates had better success this year (2024) when Senator Kirt introduced Senate Bill 1575, which would have extended the eviction timeline.53 It passed through committee but missed the deadline for a floor vote. Community advocacy for reforms is getting us closer with each passing year.

50 Id. See the infographic at the link entitled “Too Quick to Evict.” https://okpolicy.org/oklahoma-legislators-need-to-do-more-to-expand-access-to-housing/

51 Top Evicting Large Cities in the United States, The Eviction Lab, https://evictionlab.org/rankings/#/evictions?r=United%20States&a=0&d=evictionRate&lang=en

52 See H.B. 2277, http://www.oklegislature.gov/BillInfo.aspx?Bill=hb2277&Session=2300

53 See S.B. 1575, http://www.oklegislature.gov/BillInfo.aspx?Bill=sb1575&Session=2400

III. If the impact of current law is so negative, why is change difficult?

Rallying the community to action is essential because, while these harms are well-known, solutions face significant opposition. Why? Because unenforceable habitability standards, ease of eviction, and its traumatic aftereffects foster an opportunity for profit.54 And the faceless, out-of-state landlords swarming the state are willing to exploit it and fight back against reforms. A large pool of people with eviction records creates a captive market of desperate, poor tenants.55 Without enforced habitability standards, uncaring landlords can rent dangerous, ramshackle units with no consequence to desperate tenants. If those tenants cause trouble or get behind on rent, landlords can evict quickly and for cheap. In fact, landlords can even profit from eviction in some circumstances.56 Avoiding the cost of regular maintenance and using cheap, or even profitable evictions, allows for ample profits.57 Researchers call this strategy “extractive management.”58 Sadly, it is desperate people living in low-income, high crime areas who most often suffer under these extractive methods.

Low-income, high-crime neighborhoods have all the necessary elements for extractive management to profit. Broken down properties in high-crime areas are naturally the cheapest to buy. Extractive management can avoid the costs of repairs and maintenance because desperate tenants will endure mold, leaky pipes, broken windows, no air conditioning, etc. because they have nowhere else to go—other than the street.59

54 Henry Gomory & Matthew Desmond, Neighborhoods of last resort: How landlord strategies concentrate violent crime, 61 Criminology 270 (2023).

55 Gomory, supra note 5.

56 Researchers call this practice serial evictions because it results in tenants suffering multiple eviction filings a year because they often fall behind on rent but are always eventually able to pay. When filing fees are cheap enough and the eviction timeline short enough, some landlords will file to evict someone even if they know that person can come up with rent. Then, when the tenant eventually pays rent, the landlord not only collects the back rent but also collects additional fines against the tenant as part of the eviction filing, turning evictions from a last resort into an opportunity to profit. See Gomory, et al, “When it’s cheap to file an eviction case, tenants pay the price,” The Eviction Lab, (June 6, 2023) https://evictionlab.org/tenants-pay-for-cheap-evictions/

57 Id.

58 Gomory, supra note 8.

59 Id.

But these strategies don’t just exploit high-crime areas, they help cause them. Poor maintenance results in “faulty window locks, rickety doors, and malfunctioning lights,” making crimes like burglary much easier.60 High eviction rates undercut any residential stability and sense of trust and community, “a key aspect in crime prevention.”61 These landlords rarely visit their properties, making it easier to turn a blind eye to illegal activity.62 And these strategies require desperate tenants whose desperation makes them more likely to commit crime.63 Together these elements feed a cycle of poverty: (1) as a neighborhood becomes run down and crime rates increase, those with the means to leave will; (2) to make the most profit, landlords in the area turn to extractive methods to exploit those with no option but to live there; (3) these extractive methods only increase the level of crime and broken down conditions; further incentivizing extractive landlord practices.64 Forced to live in neighborhoods caught in a spiral of poverty and crime, desperate tenants—who are most often single mothers and children—are more likely to become involved in the criminal legal system.65

So, while Oklahoma’s laws allow extractive management to squeeze more profit out of renting to poor tenants, they also contribute to the concentration of poverty and crime. Those profiting from the status quo will resist reforms. But that resistance also has a solution. The reality is that Oklahoma needs landlords to rent to low-income tenants. Without landlords willing to do so, Oklahoma will never be able to fix its current lack of affordable housing. The problem is the incentives are twisted. Right now, some landlords rent to low-income tenants because the laws in Oklahoma allow them to use the “extractive” methods described above and turn a profit. But those methods hurt our communities. So, when Oklahoma reforms the laws to stop those extractive methods and protect Oklahomans, it should pair that reform with new incentives for renting to those with low-income, incentives that don’t concentrate poverty and crime. Oklahoma can expand its pre-existing affordable housing tax credit66 and pair that credit with additional credits for landlords who rent to the “hard to house”—such as large families, those with poor credit, criminal history, or prior evictions on their record. That approach would ensure landlords still have plenty of incentives to rent to the “hard to house.” In fact, the legislation to do just that has already been written.67 Housing reform is possible if we work as a community to push for policy reforms that both protect tenants and continue to incentivize landlords.

59 Id.

60 Id.

61 Id.

62 Id.

63 Id.

64 Gomory, supra note 8.

65 Id.

66 Oklahoma Affordable Housing Act, 68 O.S. § 68-2357.403.

67 See S.B. 1404 (creating robust tax incentives for landlords who rent to the hard to house: large families, those with poor credit, criminal history, and/or prior evictions on their record), http://www.oklegislature.gov/BillInfo.aspx?Bill=sb1404&Session=2400

Date

Monday, April 22, 2024 - 12:00am

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Show related content

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Show PDF in viewer on page

Style

Centered single-column (no sidebar)

Show list numbers

Author

Adam Hines

When Kerry Lalehparvaran, a Black woman, awoke late one night in January 2015 to find her boyfriend gone from their room, she got up to find where he had gone. She found him standing over her daughter, hands on her shoulders, holding her down as she whimpered. Kerry fought to get him off her, but he fought back and dragged her down the hallway. He then started spanking her daughter. Kerry put herself between her daughter and the swinging belt, but the swings kept coming. Eventually, he managed to take Kerry’s keys and phone and lock himself and her daughter in the bedroom.

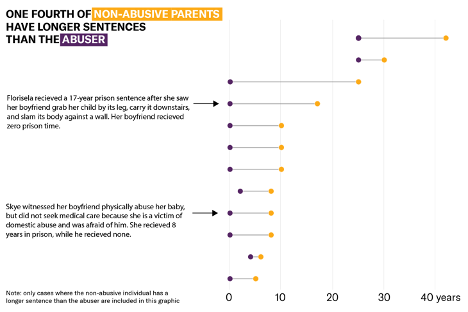

When she tried to escape the house to find help, her boyfriend heard her and physically prevented her from leaving the house. The next morning, Kerry’s roommate arrived and upon seeing the situation, fought the boyfriend, but lost when her keys and wallet were taken away. She eventually managed to escape and called the police, who arrested Kerry’s boyfriend and took her to Tulsa’s child advocacy center where the State took custody of her two youngest children, including her abused daughter. Kerry was arrested a week later for failing to protect her daughter, while her own back still bore the bruises of intercepting the swings of her boyfriend’s belt. Her boyfriend was convicted of child abuse and sentenced to 18 years in prison with 7 years of probation. Kerry was sentenced to 30 years in prison for failing to stop his abuse.

Situations like Kerry’s are common in Oklahoma, where the incarceration rate of women is the highest in the world – and has been for decades. In addition to relying heavily on incarceration to disrupt behavior, Oklahoma has a culture of holding women responsible for child-rearing. When children are abused, women are criminalized for surviving. For many women, especially women of color – whether they report or seek care for themselves – the moment they become involved with the criminal legal system, their own victimization is criminalized and their children taken away. In many cases, like with Kerry, women are victims of the same abuse for which they are incarcerated.

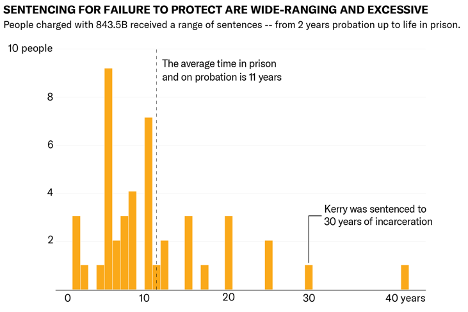

Specifically for Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect Law, where a caretaker is charged with failing to protect a child from someone else’s abuse, women are sentenced to an exuberant and wide-ranging amount of time in prison.

“I Didn’t Permit Anything” – The Incarceration of Kerry Lalehparvaran1

Long before the incident leading to her arrest, Kerry was the target of her boyfriend’s abuse. He reacted violently toward her. He threatened to kill her. On more than one occasion, he stuck a gun in her mouth. Her life was a state of constant fear and anxiety.

However, Kerry and her boyfriend were prosecuted as co-defendants. They had the same prosecutor and the same judge. The prosecutor refused to offer either of them a deal, asking for the maximum sentence for both child abuse and failure to protect – life in prison. Kerry’s boyfriend eventually pled guilty to child abuse after spending a year in jail.

Kerry decided to fight her case. “I wasn’t going to do anything but take it to trial,” Kerry said. “I wasn’t going to plead guilty to something I didn’t do….I didn’t permit anything.”2 Kerry’s case went to trial almost a year after her boyfriend was sentenced and two years after she was arrested. Despite Kerry’s boyfriend receiving a total of 25 years for child abuse, the prosecutor continued to argue that Kerry should receive life in prison for failing to stop it. To support her request for the maximum sentence, the prosecutor stated, “Well, she’s her mother.” Kerry was sentenced by a jury to 30 years in prison, a sentence that would keep her away from her children during the most important years of their lives and likely keep her locked up for the rest of her reproductive years.

Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect

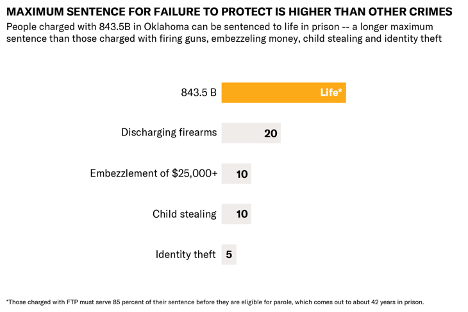

Oklahoma has criminalized the failure to prevent or report child abuse since 1963. The crime carries a maximum of life, which is high compared to other crimes.

The law applies not only to parents or guardians, but to any person. It doesn’t take into account situations like duress or experiencing domestic violence from the person committing the child abuse. While the child abuse itself must be “willful or malicious,” Failure to Protect only requires that the person “knows or reasonably should know” of a “risk” of child abuse.

To show that a person should have known of a risk of child abuse, Oklahoma prosecutors explicitly use sexist expectations of gender roles. They argue that a woman should have known the risk of child abuse under the assumption that mothers are responsible for child care and should notice immediately if anything is wrong.

Prosecutors have also argued that a woman should have known the risk because she was in an abusive relationship with the man accused of child abuse – essentially using the fact that she survived violence as evidence that she knowingly permitted child abuse. This is untrue. Domestic violence is about power and control. People enduring domestic violence are told repeatedly that the abuse and violence they are experiencing is their fault and eventually, they believe it. Because people experiencing domestic violence believe the abuse is their fault, it is not logical for them to assume that the violence is extending to their children. In their eyes, they are deserving of the abuse; their children are not.

Authors and supporters of Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect Law state it was written to incentivize people in abusive relationships to leave and that it is necessary to protect Oklahoma’s children. Experience has shown that neither is true. Leaving an abusive relationship is not as simple as walking out the door. Fear of the person responsible for the abuse,3 lack of financial resources,4 isolation from support systems,5 distrust of the legal system,6 and guilt and shame around experiencing7 abuse all act as barriers to seeking help. Deciding to leave can be extremely difficult, and leaving creates its own dangers. The risk of being killed by an abusive partner increases significantly when a person attempts to leave.8

Ultimately, Failure to Protect places an additional barrier to seeking help. People in abusive relationships fear they will be criminally prosecuted if they come forward about their abuse. They also fear losing custody of their children, which can result in foster care placement.

Who Is Incarcerated

Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect Law is used almost exclusively against women. ACLU’s Analytics team analyzed Oklahoma’s online court network data and found that women make up 93 percent of people convicted of failure to protect in Oklahoma. In the three percent of cases where a man is convicted of failure to protect, so was their female partner, because the prosecution simply did not identify the person committing the abuse and charged both caregivers with failure to protect. There were zero cases where a woman was convicted of child abuse and her male partner was convicted of failure to protect.

Not only are women held criminally responsible for the behavior of their male partners, they are often punished more harshly for it. One in four women convicted of failure to protect will receive a longer sentence than the person responsible for the abuse.

At least 50 percent of women convicted of failure to protect – including Kerry – were also abused by the same man who abused their children. Rather than receiving resources and support, they are prosecuted as co-defendants. Often, survivors of domestic violence are then incarcerated for failing to stop the crimes of their abusive partners and are separated from their children.

Kerry Lalehparvaran’s case is tragic and unjust. And it is not unique.

The ACLU, along with partnering organizations for criminal justice reform and women’s rights, are currently trying to end the criminalization of motherhood and the incarceration of survivors of domestic violence in Oklahoma. We are doing this in two ways: by attempting to reform Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect Law and by freeing women currently incarcerated for failure to protect10. In 2019, the ACLU of Oklahoma successfully freed domestic violence survivor and mother, Tondalao Hall, from prison after serving 15 years of her 30 year sentence for failure to protect. But this is only the beginning.

Countless other women like Kerry Lalehparvaran remain behind bars, and many more are faced with failure to protect charges and the accompanying threat of life in prison every day. If Oklahoma is serious about reducing the incarceration rate of women and protecting survivors of domestic violence, prosecutors must stop incarcerating women for the actions of their partners. Lawmakers must also significantly lower sentencing maximum for failure to protect and take into account the experiences of survivors of domestic violence.

The women charged with failure to protect need resources and support, not prison time, and we will continue to fight to make that a reality.

- Kerry Lalehparvaran gave Megan Lambert and the ACLU permission to publish her story as written.1

- Interview with Kerry Lalehparvaran, 7 May 2019.

- 21 Okl.St.Ann. § 843.5 Child abuse--Child neglect--Child sexual abuse--Child sexual exploitation--Enabling—Penalties. B. Any parent or other person who shall willfully or maliciously engage in enabling child abuse shall, upon conviction, be punished by imprisonment in the custody of the Department of Corrections not exceeding life imprisonment, or by imprisonment in a county jail not exceeding one (1) year, or by a fine of not less than Five Hundred Dollars ($500.00) nor more than Five Thousand Dollars ($5,000.00) or both such fine and imprisonment. As used in this subsection, “enabling child abuse” means the causing, procuring or permitting of a willful or malicious act of harm or threatened harm or failure to protect from harm or threatened harm to the health, safety, or welfare of a child under eighteen (18) years of age by another. As used in this subsection, “permit” means to authorize or allow for the care of a child by an individual when the person authorizing or allowing such care knows or reasonably should know that the child will be placed at risk of abuse as proscribed by this subsection.

- Denise Hien & Lesia Ruglass, Interpersonal partner violence and women in the United States: An overview of prevalence rates, psychiatric correlates and consequences and barriers to help seeking, 32 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 48 (2009), at 50, 51 (Fear created by [intimate partner violence] acts as a barrier to seeking help. Two of the most prevalent reasons why women did not report were fear of retribution and threats toward their children.).

- Evan Stark, Re-presenting Battered Women: Coercive Control and the Defense of Liberty, Violence Against Women (2012) at 12 (“Control tactics also foster dependence by depriving partners of the resources needed for autonomous decision-making and independent living . . . .”); Id. at 10 (“Controllers isolate their partners to prevent disclosure, instill dependence, express exclusive possession, monopolize their skills and resources, and keep them from getting help or support.”).

- Evan Stark, Re-presenting Battered Women: Coercive Control and the Defense of Liberty, Violence Against Women (2012) at 10 (“Controllers isolate their partners to prevent disclosure, instill dependence, express exclusive possession, monopolize their skills and resources, and keep them from getting help or support.”).

- Zuzana Podana, Reporting to the Police as a Response to Intimate Partner Violence, 43 Czech Sociological Review 453 (2010) (Twenty five percent of women surveyed said they didn’t report their abuse to the police because of the tendency of the police to minimize seriousness of incidents. Twenty nine percent of women do not report because of the belief that police do not take IPV seriously. Many women fear that police will make a double arrest. Ethnic minorities in particular do not report because of fear that DHS will take their children away.); Denise Hien & Lesia Ruglass, Interpersonal partner violence and women in the United States: An overview of prevalence rates, psychiatric correlates and consequences and barriers to help seeking, 32 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 48 (2009), at 15 (At the prosecution level, victims are often blamed.); Id. at 51, 52 (Poor black women are the most likely to experience re-victimization after initiating legal action, perhaps because of unresponsiveness of the police to their needs.).

- Deborah L. Rhatigan et al., The Impact of Posttraumatic Symptoms on Women's Commitment to a Hypothetical Violent Relationship: A Path Analytic Test of Posttraumatic Stress, Depression, Shame, and Self-Efficacy on Investment Model Factors, 3 Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 181 (2011) 183 (“[V]ictimized women, particularly those suffering from psychiatric conditions like PTSD or depression, may struggle to obtain adequate alternatives because of tendencies toward anger or withdrawal. Even with repeated attempts at obtaining those resources, women’s feelings of shame may increase because of negative experiences with informal or formal sources of support (i.e., via victim-blaming); Emma Williamson, Living in the World of the Domestic Violence Perpetrator: Negotiating the Unreality of Coercive Control, 16 Violence Against Women 1412 (2010) at 1417 (“Women who experience domestic violence expect to be hated because they have learned to hate themselves.”); Melissa E. Dichter, Associations Between Psychological, Physical, and Sexual Intimate Partner Violence and Health Outcomes Among Women Veteran VA Patients, 12 Social Work in Mental Health (2014) at 414 (“Sexual violence victims also often feel shame, humiliation, and degradation and experience stigmatization and blame for their victimization.”).

- Adam Pritchard et al., Nonfatal Strangulation as Part of Domestic Violence: A Review of Research, Trauma, Violence, & Abuse (2015).

- The Oklahoma Women’s Coalition advocated for legislative reform of Oklahoma’s Failure to Protect bill during the 2019 legislative session. The bill would have added an affirmative defense of duress to the crime and reduced the maximum sentence for failure to protect from life in prison to four years, the same maximum sentence as child endangerment. However, the bill was unsuccessful due to the lobbying efforts of Oklahoma’s District Attorney’s Council. Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform, through their Commutation Campaign, have applied for commutation on behalf of women incarcerated for failure to protect. Their applications will go before Oklahoma’s Pardon and Parole Board. If they receive a favorable vote from the Board, their applications will go before the Governor for his signature. Still She Rises, a holistic defense non-profit in Tulsa County, represents mothers charged with failure to protect and facing the loss of their children every day.

Methodology

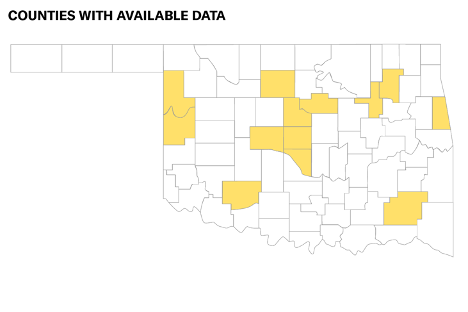

ACLU of Oklahoma contracted with Code for Tulsa to data scrape Oklahoma’s online court network (OSCN). Code for Tulsa did a search for terms relating to failure to protect for cases across Oklahoma from 2009 – 2018, the date the crime was recodified through the end of the year prior to the search.

While the data scrape included cases from all of Oklahoma’s 77 counties, only 13 counties supplied the data in a reliable and consistent format. The information given above relies upon information from those 13 counties.

ACLU of Oklahoma contacted the clerk of each county with a failure to protect conviction to request the probable cause affidavits for each case.

The cases discussed include only cases where the person was convicted of failure to protect. In none of the cases included in the analysis was the person also convicted of child abuse. In a few of the cases analyzed, the person was convicted of both failure to protect and child neglect, but only where the probable cause affidavit shows that the two charges are based on identical facts – the person’s failure to report child abuse to the police or to obtain medical care for the child quickly enough.

The gender of each person was estimated using the percentage of the US population with the same first name who are men as compared to the percentage who are women. For people sentenced to a term of incarceration, that estimate was verified by the data provided on Oklahoma’s Department of Correction’s website. The gender of a person was further verified on an individual basis by the pronouns used in the probable cause affidavit.

The information regarding the person who committed the child abuse in each was most often found because the person convicted of failure to protect and the person convicted of child abuse were prosecuted as co-defendants in the same case. When that was not the case, the person convicted of child abuse was identified in the probable cause affidavit of the failure to protect case. The details of their sentence were then found by an OSCN search.

Information about the occurrence of domestic violence was gathered in a number of ways. The first is where the person convicted of failure to protect told the ACLU of Oklahoma directly and in person during an interview. The second is where the person reported domestic violence as part of their subsequent commutation application. The third is where domestic violence was documented in the probable cause affidavit. The fourth is where the person convicted of failure to protect received a protective order against the person convicted of child abuse. Domestic violence was not recorded where a protective order was requested but not granted. Domestic violence was only recorded where the person convicted of failure to protect was a victim of the person convicted of child abuse, and not where the perpetrator of domestic violence was any other individual.

ACLU of Oklahoma manually looked up each failure to protect case on OSCN to obtain the sentencing information for the person convicted of failure to protect. While some cases included sentences for child neglect in addition to failure to protect, the data discussed above includes only the sentences for failure to protect. Deferred sentences and suspended sentences were calculated as probation. Life sentences were calculated as 42 years, the average number of years someone with a life sentence will spend in prison in Oklahoma before they are eligible for parole on an 85 percent crime.

All information discussed, with the exception of certain details of the facts leading up to Kerry Lalehparvaran’s arrest, are public record.

Date

Sunday, November 29, 2020 - 11:30am

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Related issues

People Incarcerated Rights

Criminal Justice Reform

Women's Rights

Racial Justice

Show related content

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Show PDF in viewer on page

Style

Centered single-column (no sidebar)

Show list numbers

Authors

Megan Lambert

Lindsey Feingold